I’m writing this mere hours after attending an advance screening of Wes Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme and later this week, I’ll be returning to the theater to see Mission: Impossible - The Final Reckoning in IMAX. It’s interesting to think about those films in conjunction with one another. There are the Tom Cruises of the world (as well as the Christopher Nolans, if we’re talking directors) whose main objective is ultimately to get butts in seats and keep theaters alive. It’s a respectable and necessary goal, but there’s an equally important other half to the world of auteurs and movie stars that Wes Anderson epitomizes and that he cements his place in with his latest film.

Fantastic Mr. Fox was one of my first favorite films. I didn’t know it was directed by Wes Anderson, I probably didn’t even know what directing meant or even who Wes Anderson was, but what I did know was that the vibrancy and honesty beaming through the screen was magical to me. Growing up with the film and rewatching it over the years, I’ve found its exploration of existentialism and its grappling of legacy to be even more intriguing than the stunning autumnal colors and stupendous stop-motion that paint its cinematic canvas. Everyone knows, “I think I have this thing where everybody has to think I’m the greatest, the quote unquote ‘Fantastic Mr. Fox’ and if they aren’t completely knocked out and dazzled and slightly intimated by me, I don’t feel good about myself.” It’s a Ronald Dahl quote of course and the film itself is an adaptation of Dahl’s book, but you can’t help but wonder why that is Wes Anderson’s only feature book-to-film adaptation and one of just two stop-motion films in his entire filmography. Something about that story clearly resonated with him, and he hasn’t been able to shake it since.

Watching The Phoenician Scheme for the first time, the answers to those questions as well as his entire filmography thus far completely clicked for me. Every film he’s made contributes to some grand thesis on life, death, and legacy, as well as parenthood and brotherhood as branches of those topics, and while we won’t have the full picture until the day he, God forbid, retires, it’s remarkable watching this all play out in real-time. I recently wrote about Asteroid City and Anderson’s impeccably executed contemplation on death and grief in that film, but The Phoenician Scheme is somehow even more existential, and about halfway through, something else clicked for me. The Phoenician Scheme is Wes Anderson’s take on the 1946 film A Matter of Life and Death, and you really can’t get more existential than that.

My first and only time watching Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death was in preparation for Barbie (it was on Greta Gerwig’s watchlist) so it does warrant a rewatch, but I do think it would benefit everyone to think about The Phoenician Scheme in conversation with that film. Benicio del Toro’s Zsa-zsa Korda is working within a nine-lives trope and with each step closer to his seemingly imminent final blow, he himself gets more existential and religious. He can see the face of God, but he can also see his daughter’s face for the first time in years. She’s now a mature young woman with great potential, and as they grow closer, he realizes this is the one thing in his last life that he can’t afford to screw up.

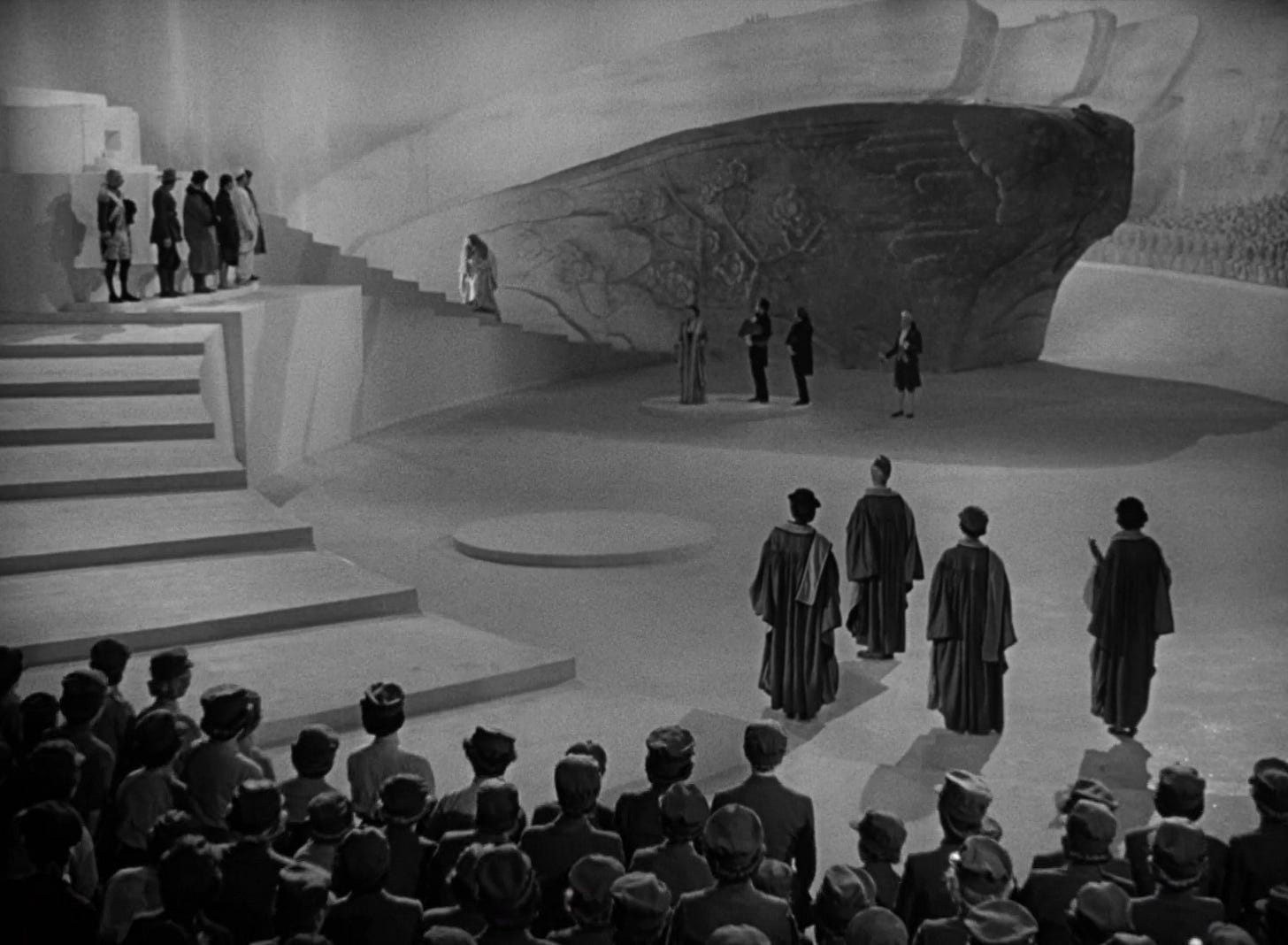

In A Matter of Life and Death, the filmmakers made the pointed decision to portray the Heaven sequences in black-and-white while the grounded sequences that take place on Earth are displayed in vibrant and utterly stunning technicolor. It’s a commentary on how the impermanence of life is what makes life worth living, and while many artists have attempted to achieve the level of earnestness that film approaches its perspective with, The Phoenician Scheme is maybe the closest I’ve seen to actually accomplishing that. It also chooses to display its afterlife scenes in monochrome, a stark contrast to Asteroid City choosing to display its “real-life” scenes that same way. It’s a fitting follow-up to Asteroid City, emerging from the pandemic with perhaps a more optimistic outlook on the fleetingness of life on Earth in the same way A Matter of Life and Death offered much-needed comfort in the aftermath of the Second World War. What if the afterlife isn’t all it’s cracked up to be? Maybe it is, but we might as well enjoy our time in these bodies and with these souls just in case.

Now, if I got into how great this cast is at pulling all of Anderson’s ideas together, we’d be here all day, but just note that the magic being made between the three leads under Anderson’s pen and watchful eye is more than worth the price of admission. They’re consistently toeing the line between comedy and contemplation masterfully, and you can feel them settling into Wes’ world more and more comfortably with each minute they share on screen. It’s hard to believe this is only Benicio del Toro’s second time on a Wes Anderson set when he’s essentially tasked with playing all of Anderson’s leads (certainly all of his patriarchs) rolled into one and still manages to do it effortlessly. And despite all the careful consideration crafting such a complex lead requires, Anderson never abandons the task of fleshing out Korda’s daughter, Liesl [cough, cough, “Christopher Nolan take notes”]. The second she opens her mouth, Mia Threapleton is unmistakably the daughter of Kate Winslet, but she proves herself over the course of the film as she keeps up with her well-seasoned co-stars, including Michael Cera who without getting into spoilers is a certain highlight who you have to imagine Anderson won’t be letting go of anytime soon.

The Phoenician Scheme is far from Wes Anderson’s best, but it’s maybe his most fascinating film yet, and certainly gives you the most to chew on if you’re thoughtful enough to do so. A Matter of Life and Death is undoubtedly a timeless film, and this doesn’t nearly reach those levels of greatness, but it would be unfair to set that expectation. It works best as a modern-day take on “optimism in the face of devastation,” particularly with the pandemic, politics, and the state of capitalism in mind. The death of capitalism is another major topic Anderson is touching on at the heart of this film, but there are so many layers to what he’s getting at here that you’ll have to check back with me in another two years for my thoughts on that.

The Phoenician Scheme won’t be an immediate all-time favorite for anyone, but I believe its place in his filmography — as a summation of his cinematic observations and perhaps a taste of what’s next — will be an interesting concept to sit with over time. I’m also a firm believer that directors don’t always have to be churning out masterpieces. In my personal opinion and in terms of directors with large bodies of work, only James Cameron and Martin Scorsese have maintained such an unattainable level of quality in tandem with consistency. Even I have to admit that my two favorite directors in Spielberg and Hitchcock have had their duds. However, even those middle-of-the-road “lows” in their oeuvres were made watchable and worthy because of the director’s vision behind them. Maybe executives interfered, maybe production fell apart, but there are always at least glimpses of that familiar greatness that ultimately make even their worst films more interesting than the large majority of what’s being put out by Hollywood at any point in time. Wouldn’t you rather consume the work of a singular auteur than mindless and colorless studio slop that could have been made by anyone?

Wes Anderson is the director who made me believe in the magic of cinema, so while encouraging the pursuit of moviegoing for a financial end is imperative in this day and age, implementing and keeping the spirit of movies alive (regardless of whether they have all the glitter and gold of a Cruise or a Nolan) is just as essential to the future of cinema. After seeing The Phoenician Scheme, I can confidently say that Wes Anderson has done his tried-and-true job of filling that void once again.

Opinions on Anderson’s career trajectory have been mixed, but I’m of the camp that he’s only getting better with time. Each year he spends on this Earth gives him more to contemplate and only strengthens his overarching themes of existentialism. This film, like many of his recent films, is a grappling on legacy and the world we leave for the next generation. I don’t think the doomsdaying around The Phoenician Scheme not being his magnum opus is worth it when he clearly seems to have his best ahead of him and will only have more to say as he gets older and wiser. If you don’t like Wes Anderson’s work, especially anything he’s made in the past decade, this film won’t be for you and I won’t make you waste your time. However, if you’re as on board with his wild exploration of existentialism as I am, The Phoenician Scheme has plenty to offer — thoughts, prayers, and hand grenades, lots and lots of hand grenades.